27. October 2015

Dūnhuáng - Resting in the Old Oasis

Arriving here on the 24th of October, Dūnhuâng was not only my most western place in China, but also more or less exactly the halfway point for my time in China and the journey in total. Historically Dūnhuáng had been an important oasis town on the Silk Road, were the northern and the southern route from the west joined again and even today you can easily envision the people once bartering and discussing here.

Apart from the major spots (which I will talk about in a second), Dūnhuáng has more to offer to the traveller. While most hostels had already been closed at this time of the year due to the harsh winter here being even less pleasant than the blistering summer, the live on the street still continued. The vibrant markets selling fruits and nuts were even more prevalent than in the previous cities and while wandering around in the morning the sight of locals practicing their skills with the whip had replaced the silent, slow moves of t’ai chi.

Originally I planned, reminding myself of the travellers some centuries ago, to mostly relax for a few days and gather new strength for the second half of my trip. As you may guess from the missing blog updates during this time, I did not really stick to this plan. While I certainly wanted to visit the sand dunes (Míngshā Shān), I did not know that I would visit them three times during the four days spent in Dūnhuáng. And having met some very nice people – a Chinese-British and a Japanese couple – my evenings went by quite quickly as well.

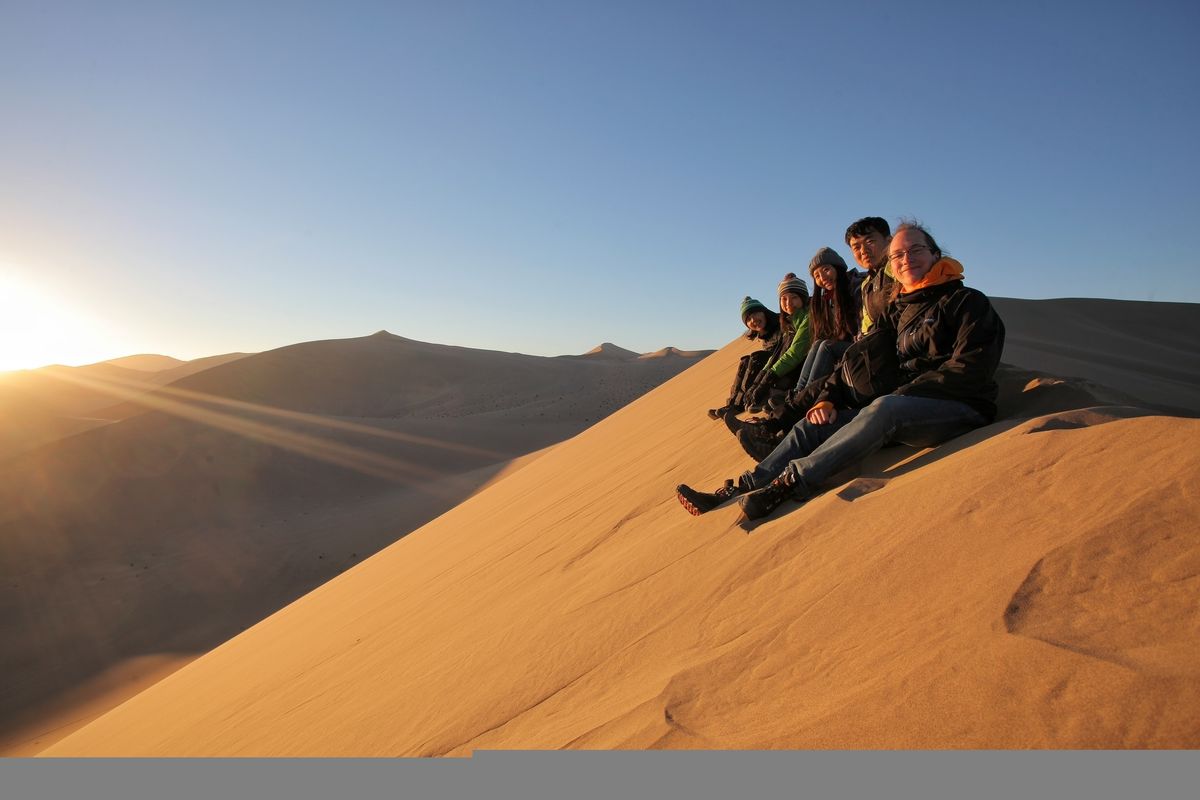

One morning we (except for Neil, who had a slight cold) climbed one of the dunes together to catch the sunrise near the peak. Unfortunately the dunes near the city have been turned into a touristic site, meaning that – apart from having yo pay the admission fee – people try to sell you camel and jeep rides and of course you can only enter during the opening hours and you are only allowed to walk in the marked area.

This didn’t really fit to our plans put fortunately that’s not the only way to see the dunes. Together with another traveller, who had taken this path already, we walked around the entrance and along the fence for some while. The light from the moon was illuminating the small road, but although it was not completely dark, we still got surprised when suddenly some camels were trotting past us, being brought to the entrance area to carry the tourists for a short walk. Not long afterwards we found the hole under the fence and sneaked in to explore the dunes without further disturbances.

The hike itself was a bit exhausting. It takes a bit of time to get used to walking on sand. With every step you sink in and the faster you try to get, the more you have to pull your feet out again. But slowly we moved forward. Suddenly we heared some noise. Fearing the park security had noticed something, we cowered in the shadows for a minute before we continued our climb a bit more cautiously. Maybe we just have heared the phenomena of the singing sands: If the sand has a certain structure, it may resonate due to either wind or surrounding sounds. The dunes of Dūnhuàng are supposed to be singing, but during the day I was never able to hear them – maybe due to the lack of wind after sunrise.

We reached a nice spot and sat down to wait a few more minutes. Finally the sun rose itself over the horizon, bathing us and the sand in warming rays of light. We cheered, not only because the chill of the night faded fast in the light, but because the experience of having successfully hiked here together. Of course we also took some photos, but mostly we were just watching: watching the dunes, watching the crescent moon lake and watching other tourists in the far distance, who had taken the more convenient path.

While Míngshā Shān is impressive, it’s not the only amazing site around Dūnhuáng. 366 AD a Buddhist monk created the first of thd Mògao Caves, starting a work which should grow long past his time. Over the centuries hundreds of caves were carved into the rocks, sponsored by wealthy merchants, reflecting the changes in Buddhist art as time and dynasties went by.

With the the reciding of the water around Dūnhuáng, the importance of this major stop along the silk road rapidly declined as well and the Mògao Caves were completely forgotten. After being hidden for hundred of years, they were rediscovered in the early 20th century and are now among the most important sites for Buddhist art.

Only very few of the caves are open for tourists and the number of visitors per day is strictly limited to prevent further damage of the fragile paints, but the site is well organized. Before the tourists are transported to the caves themselves, two impressive movies (one of them in a 360° cinema) are shown to them, explaining the history and some of the most important aspects.

The Mògao Caves must also be one of the few places in China where being a foreign tourist is a definite advantage. While the group size per guide is limited in general to 25 people, at this time of the year there was not even this number of foreigners on the day I visited the caves. To be a bit more exact: Apart from me there was only one other foreigner, meaning we had an English speaking guide all for ourselves. As a result the tour was much less rushed and since the guide noticed our interest, we were even shown more caves than the other tours (at normally a group is only guided through 8 caves).

Sorry, I unfortunately can’t show you any photos of the caves, since photographing is not allowed there. I assume it’s mostly to prevent tourists without a real grasp for their camera - so most of them - to accidentally use a flash. To not encourage others to try to take photos despite it being prohibited, I did not even ask our guide whether I could take photos without a flash.)